-

From the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery

Femorofemoral bypass with femoral popliteal vein

Victor D’Addio, MD,a Ahsan Ali, MD,b Carlos Timaran, MD,a Tif Siragusa, MD,a James Valentine, MD,a Frank Arko, MD,a J. Gregory Modrall, MD,a and G. Patrick Clagett, MDa Dallas, Tex; and Little Rock, Ark

Background: The femoropopliteal vein (FPV) has been used successfully for vascular reconstructions at multiple sites. To date, there have been no studies documenting patency of the FPV graft in the femorofemoral position. Our goal was to assess long-term patency of the FPV graft used for femorofemoral bypass (FFBP). Methods: Patients undergoing FFBP over a 10-year period were studied. Those in whom the FPV was used as a conduit were analyzed for runoff resistance score to assess how patients with poor runoff fared. Poor runoff was defined as a runoff resistance score of >7 (1 normal runoff, 10 total occlusion of all runoff vessels).

Results: Fifty-four patients underwent FPV FFBP as a sole procedure (n = 16, 30%) or as a portion of an aortofemoral reconstruction with a FFBP component (n = 38, 70%). Mean ( SD) follow-up was 47 ± 33 months. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year primary patencies were 97%, 93%, and 76%. The 5-year assisted primary and secondary patency rates were 85% and 90%. Among 27 patients with poor runoff (runoff resistance score of >7), the cumulative 40 month patency rate was 90%. Among patients in whom FPV FFBP was performed as a primary procedure (no aortofemoral component), there were no graft failures.

Conclusions: FFBP performed with FPV has excellent 1-, 3, and 5-year patency rates. FPV has sustained patency for FFBP in patients with poor runoff. ( J Vasc Surg 2005;42:35-9.)

The role of femorofemoral bypass (FFBP) has changed. When first described by Vetto in 1962,1 FFBP was in- tended for use in debilitated patients with unilateral iliac occlusive disease who were too ill to undergo an aortic- based procedure. Contemporary FFBP is often used to treat complex vascular problems associated with failed aor- toiliac/femoral bypasses or failed endovascular therapies. This bypass, although ideal for high-risk patients, has been characterized by patency rates inferior to in-line reconstruc- tive techniques.2,3

The femoral popliteal vein (FPV) graft has been used successfully as a conduit in many vascular beds.4-12 In 1997, we reported 5-year primary and assisted primary patency rates of 84% and 100%, respectively, for aortoiliac/ femoral reconstructions with FPV grafts in the treatment of infected aortic prostheses.4 Almost half of these reconstruc- tions involved a unilateral aortofemoral bypass coupled with a FFBP, both fashioned from FPV grafts. Because of the favorable experience with the FFBP in these patients, we expanded the use of FPV grafts for FFBPs.

In this report, we review our entire experience with FPV grafts for FFBPs, with a focus on durability. Because runoff is a major determinant of patency in these recon- structions, we performed a separate analysis of patients with FPV grafts who had compromised runoff.

From the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center,a and University of Arkansas Medical Center.b

Competition of interest: none.

Presented at the Twenty-ninth Annual Meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, Marco Island, Fla, Jan 19-22, 2005.

Reprint requests: G. Patrick Clagett, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390-9157.

0741-5214/$30.00

Copyright © 2005 by The Society for Vascular Surgery. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.056METHODS

The records of all patients who underwent a FFBP over a 10-year period in a single university-based practice were examined. These cases were indexed from an institutional computerized registry of operative cases. Study data were obtained from inpatient and outpatient treatment records. The data from all patients with FPV grafts were entered into a registry that included operative details, course, and out- comes as well as a prospective follow-up program.

The follow-up consisted of a return visit within 1 month after discharge, at 3-month intervals for the first postoperative year, and at 6-month intervals thereafter. Follow-up was conducted with clinical examination, non- invasive vascular studies, and duplex ultrasound examina- tion.

Duplex findings suggesting a hemodynamically signif- icant stenosis consisted of a focal increase in peak systolic flow velocity that, when indexed against the peak systolic flow velocity in adjacent proximal or distal segments, yielded a ratio of 3.0. These findings, as well as a return of symptoms or a significant change in ankle systolic pressures, prompted further evaluation with computed tomographic or conventional arteriography.

Patients underwent preoperative duplex vein mapping to assess patency, diameter, and available length of FPV. The FPV was considered adequate for use if it was 6 mm in diameter and had no significant evidence of previous deep venous thrombosis.

The technique of FPV harvest has been described in detail elsewhere.13,14 Briefly, the vein is exposed in the subsartorial canal through an incision over the lateral bor- der of the sartorius muscle. After ligation of side branches, the vein is left in situ until a measurement of required length can be performed. The common femoral artery is also exposed through this lateral incision.

D’Addio et al

JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY

July 2005

Once the required length of vein graft is determined, the vein is harvested taking care to divide the proximal vein flush with the junction of the profunda femoris and com- mon femoral veins so that no stump is left as a source for thrombus formation. The vein is flushed thoroughly, everted, and the valves excised. The FFBP tunnel is created in the subcutaneous tissues of the lower abdomen. Anasto- moses are performed in standard end-to-side fashion.

Demographic data, comorbidities, indication for oper- ation, and patency rates were examined for both groups. The runoff resistant scores15 were calculated to examine patency rates in patients with poor runoff. According to this system, a minimum value of 1 indicates excellent runoff with no distal disease, and a maximum value of 10 denotes no runoff (blind vascular segment).15 Poor runoff in this report is defined as a runoff resistance score of > 7. Patency was also examined in another subgroup of patients who had FPV FFBP as a primary operation (no concomitant aortic inflow procedure). Primary patency was defined according to Society for Vascular Surgery recommended reporting standards.15 Patency rates and limb salvage were described using the Kaplan-Meier survival method.

RESULTS

During the study period, 54 patients underwent FPV FFBP: 38 (70%) had an aortobifemoral bypass performed with two FPV grafts, an aortofemoral segment, and a FFBP segment; 16 (30%) had FPV FFBP as a solitary procedure. The demographic, comorbidity data, and the operative indications are shown in Table I. Most (n 38) of these procedures were done for either graft infection or throm- bosis of a previously placed prosthetic graft, and 36 (95%) of these 38 patients had occlusive disease. All patients who had FFBP as a sole procedure (n 16) had occlusive disease. The mean follow-up time was 47 ± 33 months among surviving patients. Follow-up was complete in 49 patients (91%); the remaining five patients either died or were lost to follow-up.

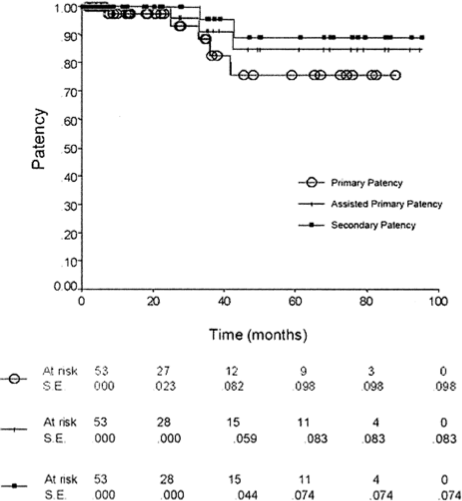

Primary patency rates at 1, 3 and 5 years for patients undergoing FPV FFBP were 97%, 93%, and 76% (Fig). Assisted primary patency and secondary patency rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 100%, 91%, and 85% and 100%, 95%, and 90%, respectively (Fig).

None of the 16 patients who had FPV FFBP only (without concomitant aortic inflow procedure) required graft revision or had thrombosis of the graft. The primary patency for this group was 100%, with a mean follow-up of 36 ± 29 months.

There were five failures, and all were patients who had complete aortofemoral reconstructions performed because of aortic graft infection. Three patients had asymptomatic graft stenoses detected on routine duplex surveillance, two of whom underwent surgical revision with vein patch an- gioplasty at 7 and 12 months after operation. The third patient had stenting of a stenotic area in the FFBP 36 months after operation. All three grafts remain open. A fourth patient had FFBP thrombosis at 25 months after operation and required thrombectomy and distal anasto-motic revision. This graft also has remained open since revision. A fifth patient had graft thrombosis at 43 months after operation and required amputation for nonreversible lower extremity ischemia.

Table I. Demographics, comorbidities, and operative indications

Demographics

Number of patients54

Female gender25(46%)

Median age60

Comorbidities

HTN44(81%)

CAD23(43%)

DM14(26%)

COPD2(4%)

ESRD2(4%)

CRI2(4%)

Hyperlipidemia21(39%)

Tobacco use38(70%)

Operative indications

Graft infection38(70%)

Lower extremity ischemia9(17%)

Lower extremity ischemia

secondary to graft occlusion11(20%)

HTN, Hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; CRI, chronic renal insufficiency.

Fig.

Kaplan-Meieranalysisshowingprimary,primaryassisted,and secondary patency for femoropopliteal vein femorofemoral bypass.Information was available to calculate runoff resistance scores in 49 of the 54 patients who had FPV FFBP. Of these, 26 patients (53%) had scores of > 7 and were consid- ered to have poor runoff. Nine of these 26 patients had concomitant lower extremity bypasses at the time of FFBP.

JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY

Volume 42, Number 1D’Addio et al

Table II. Published 5-year primary, assisted primary, secondary patency, and graft infection rates (when reported) of femorofemoral bypass with varying conduit types.

Conduit type

Study

No. of patients

Study period (yrs)

5-yr primary patency (%)

Graft infection rate (%)

Assisted primary patency (%)

Secondary patency (%)

Prosthetic

Plecha(1984)17

Lamerton (1985)18

Criado (1993)19

Schneider (1994)3

Mingoli (2000)20119

54

110

91

22810

10

11

5

2072

60

60 (3 yr)

61

705

NR

3.6

NR

NRNR

NR

NR

NR

NRNR

NR

NR

70

80Aortouniiliac stent graft

Hinchcliffe (2003)21

Lipsitz (2003)22231

1108

883

954.3

0NR

NRNR

NRGreater saphenous vein

Hakaim (1994)23

Jicha (1995)2425

3413

1175 (3 yr)

524

NRNR

NRNR

70Femoropopliteal vein

Current study (2004)

54

10

76

0

85

90

The 1-year and 40-month patency rates for patients with poor runoff were 100% and 90%, respectively. Beyond 40 months, the Kaplan-Meier survival curve was unreliable, with the standard error > 10%.

Sixteen (30%) of the 54 patients who had FPV FFBP had postoperative morbidity. Nine patients had postoper- ative wound problems at vein harvest sites (5 wound dehis- cences and 4 wound infections requiring antibiotic ther- apy). Additional morbidity included two cases of renal failure, two cases of pancreatitis, one myocardial infarction, and a single episode each of peritonitis and Clostridium difficile colitis. Almost all morbidity occurred in patients being treated for aortic graft infection. There were three deaths, all in patients who required treatment for aortic graft infection. The 30-day mortality was 5.5%.

There was no long-term venous morbidity from vein harvest, including symptoms of venous claudication or venous stasis ulceration. There was short-term venous mor- bidity, primarily manifested by the requirement for fas- ciotomy. Of 78 limbs that had FPVs harvested, 27 (35%) underwent fasciotomy. This was assessed clinically at the time of the initial procedure, and fasciotomy was performed concurrently. All but one of the fasciotomies was per- formed in patients undergoing FFBP as part of the opera- tive treatment of an aortic graft infection. There were 16 limbs at risk in patients who underwent FPV FFBP as a sole procedure, and one fasciotomy (6%) was performed in this group. The patient who required fasciotomy had concom- itant harvest of the ipsilateral greater saphenous vein.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that FFBP with FPV is a durable procedure with 5-year primary, assisted primary, and sec- ondary patency rates of 76%, 85%, and 90%, respectively. Excellent patency was achieved in a high-risk population of patients, many of whom had active graft infection, failure or thrombosis of vascular grafts, and poor runoff. There is one other report describing outcomes of FPV FFBP. Me- neghetti et al16 reported 20 of these reconstructions in selected patients with either prosthetic graft infection or

poor runoff. With a mean follow-up of 24 months, the authors concluded that the FFBP was an effective conduit in these disadvantaged patients, although formal patency rates were not reported.

There is a large body of literature that examines out- comes of prosthetic FFBP (Table II). Reported 3- to 5-year patency rates range from 60% to 72% when FFBP is done for occlusive disease. Patients who have undergone previ- ous aortofemoral bypass and who require FFBP for unilat- eral limb occlusion have worse patency than those who undergo prosthetic FFBP as a primary procedure.25-27 In addition, patients with poor runoff fare worse than those with good runoff.28 Patients who undergo FFBP as part of an aortouniiliac stent graft procedure have higher FFBP patency rates that range from 83% to 95% at 5 years21,22,29,30 (Table II). This is most likely reflective of good runoff in patients with aneurysmal disease.

There are fewer reports of patients undergoing FFBP with greater saphenous vein (Table II).23,24 It is interesting to note that patency rates with this autogenous conduit appear inferior to those of prosthetic FFBP. This mirrors our own disappointing experience with greater saphenous vein reconstructions following removal of infected aortic prostheses.4 We noted that the smaller greater saphenous vein grafts were subject to kinking and distortion as well as were more likely to be compromised by small amounts of intimal hyperplasia compared with large caliber FPV grafts.4

Excellent patency (90% at 40 months) in patients with FPV FFBP was realized in patients with poor runoff as determined by calculated runoff resistance scores. In addi- tion, the subgroup of patients who had FPV FFBP as a primary procedure had 100% primary patency at 5 years. These values are the highest reported patency rates to date for FFBP in patients with occlusive disease and exceed those reported for prosthetic FFBP (Table II).

Another advantage of the FPV FFBP is the low infec- tion rate. There were no cases of FPV graft infection in this series despite the large number of patients who underwent the procedure for graft infection. The overall infection rate for prosthetic FFBPs is 2% to 5% (Table II), among the highest for vascular prostheses at any location.

D’Addio et al

JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY

July 2005

The disadvantages of using the FPV for FFBP include the additional operative time for harvest, the potential for compartment syndrome, and the need for fasciotomy. Long-term venous morbidity is rare31 and was not seen in this series. Almost all cases of fasciotomy in patients under- going FPV FFBP were in those with infected aortic pros- theses who had concomitant FPV aortofemoral bypass with recognized risk factors for compartment syndrome, includ- ing severe pre-existing lower extremity ischemia, prolonged aortic cross-clamp time, and massive crystalloid require- ments.32 The only patient undergoing FPV FFBP as a primary procedure who required fasciotomy had concom- itant harvest of the ipsilateral greater saphenous vein, an- other recognized risk factor for compartment syndrome.32

In conclusion, we believe that we have shown that FFBP with FPV is a durable procedure and that the FPV may be the best conduit for this operation in patients with extensive occlusive disease. That is not to say that prosthetic FFBP does not have a role. It will continue to be useful in patients with favorable anatomy and runoff, such as those with aneurysmal disease, particularly those undergoing aor- touniiliac stent graft placement.21,22,29,30 However, in pa- tients with occlusive disease and poor runoff as well as in complex patients with graft infections or failure of previous interventions, FPV FFBP is a durable procedure.

REFERENCES

1. Vetto R. The treatment of unilateral iliac artery obstruction with a transabdominal, subcutaneous, femorofemoral graft. Surgery 1962;52: 342-5.

2. Perler B, Burdick J, Willimas G. Femoro-femoral or ilio-femoral bypass for unilateral inflow reconstruction? Am J Surg 1991;161:426-30.

3. Schneider J, Besso S, Walsh D, Zwolak R, Cronenwett J. Femorofemo- ral versus aortobifemoral bypass: outcome and hemodynamic results. J Vasc Surg 1994;19:43-57.

4. Clagett G, Bowers B, Lopez-Viego M, Rossi M, Valentine R, Myers S, et al. Creation of a neo-aortoiliac system from lower extremity deep and superficial veins. Ann Surg 1993;218:239-49.

5. Hagino R, Bengston T, Fosdick D, Valentine R, Clagett G. Venous reconstructions using the superficial femoral-popliteal vein. J Vasc Surg 1997;26:829-37.

6. Gordon L, Hagino R, Jackson M, Modrall J, Valentine R, Clagett G. Complex aortofemoral prosthetic infection: the role of autogenous superficial femoropopliteal vein reconstruction. Arch Surg 1999;134: 615-21.

7. Modrall J, Joiner D, Seidel S, Jackson M, Valentine R, Clagett G. Superficial femoral-popliteal vein as a conduit for brachiocephalic arte- rial reconstructions. Ann Vasc Surg 2002;16:17-23.

8. Modrall J, Sadjadi J, Joiner D, Ali A, Welborn M, Jackson M, et al. Comparison of superficial femoral vein and saphenous vein as conduits for mesenteric arterial bypass. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:362-6.

9. Clagett G, Valentine R, Hagino R. Autogenous aortoiliac/femoral reconstruction from superficial femoral-popliteal veins: feasibility and durability. J Vasc Surg 1997;25:255-70.

10. Jackson M, Ali A, Bell C, Modrall J, Welborn M, Scoggins E, et al. Aortofemoral bypass in young patients with premature atherosclerosis: is superficial femoral vein superior to Dacron? J Vasc Surg 2004;40:17- 23.

11. Huber TS, Hirneise CM, Lee WA, Flynn TC, Seeger JM. Outcome after autogenous brachial-axillary translocated superficial femoropopli- teal vein hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:311-8.

12. SchulmanML,BadheyMR,YatcoR.Superficialfemoral-poplitealveins and reversed saphenous veins as primary femoropopliteal bypass grafts: a randomized comparative study. J Vasc Surg 1987;6:1-10.

13. ClagettG.Updateonsurgicalmanagementofinfectedaorticgrafts.In: Pearce W, Matsumura J, Yao J, editors. Trends in vascular surgery. Chicago: Precept Press, 2003; p.199-211. 14. Valentine R. Harvesting the superficial femoral vein as an autograft. Semin Vasc Surg 2000;13:27-31.

15. Rutherford R, Baker J, Ernst C, Johnston K, Porter J, Ahn S, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity isch- emia: revised version. J Vasc Surg 1997;26:517-38.

16. Meneghetti A, MacDonald P, Reid J, Sladen J, Turnbull R. Patency of superficial femoral vein employed as a crossover femoral artery bypass conduit. Ann Vasc Surg 2002;16:746-50.

17. Plecha F, Plecha F. Femorofemoral bypass graft: ten-year experience. J Vasc Surg 1984;1:555-61.

18. Lamerton A, Nicolaides A, Eastcott H. The femorofemoral graft. Arch Surg 1985;120:1274-8.

19. Criado E, Burnham S, Tinsley E, Johnson G, Keagy B. Femorofemoral bypass graft: analysis of patency and factors influencing long-term outcome. J Vasc Surg 1993;18:495-505.

20. Mingoli A, Sapienza P, Feldhaus R, di Marzo L, Burchi C, Cavallaro A. Femorofemoral bypass grafts: factors influencing long-term patency rate and outcome. Surgery 2001;129:451-8.

21. Hinchcliffe R, Alric P, Wenham P, Hopkinson B. Durability of femo- rofemoral bypass grafting after aortouniiliac endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2003;38:498-503.

22. LipsitzE,OhkiT,VeithF,RheeS,GarguiloN,SuggsW,etal.Patency rates of femorofemoral bypasses associated with endovascular aneurysm repair surpass those performed for occlusive disease. J Endovasc Ther 2003;10:1061-5.

23. Hakaim A, Hertzer N, O’Hara P, Krajewski L, Beven E. Autogenous vein grafts for femorofemoral revascularization in contaminated or infected fields. J Vasc Surg 1994;19:912-5.

24. Jicha D, Reilly L, Kuestner L, Stoney R. Durability of cross-femoral grafts after aortic graft infection: the fate of autogenous conduits. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:393-407.

25. RutherfordR,PattA,PearceW.Extra-anatomicbypass:acloserview.J Vasc Surg 1987;6:437-46.

26. Nolan K, Benjamin M, Murphy T, Pearce W, McCarthy W, Yao J, et al. Femorofemoral bypass for aortofemoral limb occlusion: a ten-year experience. J Vasc Surg 1994;19:851-7.

27. Kalman P, Hosang M, Johnston K, Walker P. The current role for femorofemoral bypass. J Vasc Surg 1987;71-6.

28. Criado E, Burnham S, Tinsley E, Johnson G, Keagy B. Femorofemoral bypass graft: analysis of patentcy and factors influencing long-term outcome. J Vasc Surg 1993;495-505.

29. Clouse W, Brewster D, Marone L, Cambria R, LaMuraglia G, Watkins M, et al for the EVT/Guidant Investigators. Durability of aortouniiliac endografting with femorofemoral crossover: 4-year experience in the EVT/Guidant trials. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1142-9.

30. Yilmaz L, Abraham C, Reilly L, Gordon R, Schneider B, Messina L, et al. Is cross-femoral bypass grafting a disadvantage of aortomonoiliac endovascular aortic aneurysm repair? J Vasc Surg 2003;38:753-7.

31. Wells J, Hagino R, Bargmann K, Jackson M, Valentine R, Kakish H, et al. Venous morbidity after superficial femoral-popliteal vein harvest. J Vasc Surg 1999;29:282-91.

32. Modrall J, Sadjadi J, Ali A, Anthony T, Welborn M, Valentine R, et al. Deep vein harvest: predicting need for fasciotomy. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39:387-94.

Submitted Jan 27, 2005; accepted Mar 31, 2005.

JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY

Volume 42, Number 1D’Addio et al

DISCUSSION

Dr Thomas Naslund (Nashville, TN). The authors have provided a summary of their experience with the use of femoral- popliteal vein as a femorofemoral bypass conduit. Their experience with this conduit is unparalleled, and their continued publication of its use over the last decade is commendable. An important avenue of therapy has been tapped by evaluating the use of the femoral-popliteal vein graft for isolated femorofemoral bypass. The authors have demonstrated a patency superior to their own expe- rience with synthetic grafts and provide a contribution to the literature by establishing this technique for consideration by all. Although their data show patency benefit, we must be reminded that this benefit was realized by comparing vein with a 40% 5-year patency of synthetic femorofemoral bypass grafts.

I would like to ask three questions: First, do you currently utilize femoral-popliteal vein as the choice conduit for femorofemoral bypass in your institution? In answering that question, I would like for you to comment on your indication for use of synthetic bypass grafts.

Second, do you consider patients with previous saphenous vein harvest candidates for femoral-popliteal vein grafts for routine femorofemoral bypass, and should such patients undergo prophy- lactic fasciotomy at the time of procedure?

And finally, what increase in operative time is anticipated in the use of femoral-popliteal vein as opposed to synthetic graft for femorofemoral bypass?

I appreciate the opportunity to make comment on this fine paper and thank the Association for the opportunity to do so.

Dr Victor D’Addio. Response to question 1. We preferen- tially use femoral-popliteal vein (FPV) for femorofemoral bypass (FFBP) in patients who have thrombosed previously placed aorto- femoral or femorofemoral prosthetic grafts, have a graft infection involving the groins, or have a remote site of infection. In addition, we use the FPV in patients with compromised runoff. As an institution, we have become very comfortable with use of FPV in multiple vascular beds, and based on our positive experience with

this specific conduit, we do use it primarily in some patients. Prosthetic FFBP clearly still has a role in patients who require this extra-anatomic reconstruction. It is best used for patients with favorable runoff, such as patients who have aneurysmal disease and require FFBP after aortouniiliac stent grafting.

Response to question 2. Patients who have had previous greater saphenous vein (GSV) harvest continue to be candidates for harvest of the ipsilateral FPV, so we do not consider previous GSV harvest a contraindication to harvest of the FPV. As our data show, the risk of fasciotomy is low in patients undergoing FFBP as a sole procedure. Only one patient who underwent FFBP with FPV as a sole procedure required fasciotomy, and this patient under- went concomitant GSV harvest. Concomitant harvest of the GSV is indeed a risk factor for the requirement of fasciotomy, as previ- ously published by Modrall et al.32

The other major factor that affects the need for fasciotomy is the degree of lower extremity ischemia preoperatively. Patients with an ankle-brachial index (ABI) of < 0.4 were found to require fasciotomy significantly more often than those patients with higher ABIs. Other factors that may affect the need for fasciotomy are length of vein harvested, volume of intraoperative fluid, and dura- tion of operative ischemia.

We do not perform prophylactic fasciotomy. The decision to perform a fasciotomy is based on intraoperative physical assessment of the lower extremity after revascularization along with consider- ation of the previously mentioned factors.

Response to question 3. There is an increase in operative time when the FPV is used as a conduit. Harvest and preparation of the vein take approximately 2 hours. The specific technique of harvest is given in the article. The valves in the vein are directly lysed after everting the vein, and this requires time in addition to the actual harvest time. We have found that because of the large caliber of the vein, use of a valvulotome is inadequate for valve lysis and have gone to direct valve lysis. This takes a bit longer but prevents stenoses at inadequately lysed valve sites.

3/10/2021

Victor D’Addio, MD,a Ahsan Ali, MD,b Carlos Timaran, MD,a Tif Siragusa, MD,a James Valentine, MD,a Frank Arko, MD,a J. Gregory Modrall, MD,a and G. Patrick Clagett, MDa Dallas, Tex; and Little Rock, Ark

Published July 2005

Victor D’Addio, MD,a Ahsan Ali, MD,b Carlos Timaran, MD,a Tif Siragusa, MD,a James Valentine, MD,a Frank Arko, MD,a J. Gregory Modrall, MD,a and G. Patrick Clagett, MDa Dallas, Tex; and Little Rock, Ark

Femorofemoral bypass with femoral popliteal vein

Summary

Vascular diseases like aortic graft infection, ischemia, thrombosis, occlusive disease form a blockage in arteries. The standard method to remove arterial blockages is an aortic-based procedure.

But with patients who are too ill or have comorbidities like obesity, blood pressure, diabetes, etc FFBP(Femorofemoral bypass with femoral popliteal vein) is the best surgical procedure to resolve arterial blockages and treat aortic graft infections.