-

From the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery

Delayed management of Grade III blunt aortic injury: Series from a Level I trauma center

Matthew R. Smeds, MD, Mark P. Wright, MD, John F. Eidt, MD, Mohammed M. Moursi, MD, Guillermo A. Escobar, MD, Horace J. Spencer, and Ahsan T. Ali, MD

BACKGROUND: Blunt aortic injuries (BAIs) are traditionally treated as surgical emergencies, with the majority of repairs performed in an urgent fashion within 24 hours, irrespective of the grade of aortic injury. These patients are often underresuscitated and often have multiple other trauma issues that need to be addressed. This study reviews a single center's experience comparing urgent (<24 hours) thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR) versus delayed (>24 hours) TEVAR for Grade III BAI.

METHODS: All patients undergoing TEVAR for BAI at a single institution between March 2004 and March 2014 were reviewed (n = 43). Patients with Grade I, II, or IV aortic injuries as well as those who were repaired with an open procedure or who lacked preoperative imaging were excluded from the analysis. Demographics, intraoperative data, postoperative survival, and complications were compared.

RESULTS: During this period, there were 43 patients with blunt thoracic aortic injury. There were 29 patients with Grade III or higher aortic injuries. Of these 29 patients, 1 declined surgery, 2 were repaired with an open procedure, 10 underwent urgent TEVAR, and 16 had initial observation. Of these 16, 13 underwent TEVAR in a delayed fashion (median, 9 days; range, 2–91 days), and 3 died of non–aortic-related pathology. Comparing the immediate repair group versus the delayed repair group, there were no significant demographic differences. Trauma classification scores were similar, although patients in the delayed group had a higher number of nonaortic injuries. The 30-day survival was similar between the two groups (9 of 10 vs. 12 of 16), with no mortalities caused by aortic pathology in either group.

CONCLUSION: Watchful waiting may be permissible in patients with Grade III BAI with other associated multisystem trauma. This allows for a repair in a more controlled environment. (J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80: 947–951. Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.)

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Therapeutic study, level V.

KEY WORDS: Aortic transection; TEVAR; trauma; blunt aortic injury

Up to 75% of deaths caused by blunt trauma are secondary to chest injuries, with the majority of these deaths arising in patients with thoracic aortic injuries.1 With the advent of a minimally invasive approach to the aorta via thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR), TEVAR has rapidly become a standard of care in the treatment of these injuries, negating the need for an open thoracotomy, aortic clamping, anticoagulation, or left-sided heart bypass. This has improved survival and decreased the risks of dreaded complications such as spinal cord ischemia, renal failure, and systemic infections.2–5 A grading system currently in use classifies patients into one of four groups, depending on the severity of the aortic trauma. Grade I injuries are limited to intimal tears, Grade II injuries have intramural hematomas, Grade III injuries have pseudoaneurysm, and Grade IV injuries have free rupture.6

Submitted: July 13, 2015, Revised: February 12, 2016, Accepted: February 15, 2016,

Published online: March 7, 2016.

From the Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (M.R.S., M.P.W., M.M.M., G.A.E., H.J.S., A.T.A.), Department of Surgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas; and Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute (J.F.E.), Baylor Medical Center, Dallas, Texas.

This study was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Vascular Surgery, June 2012, in Washington, District of Columbia.

Address for reprints: Ahsan T. Ali, MD, Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham St. #520-2 Little Rock, AR 72205; email: sibiahsan@yahoo.com.

DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001027It has been fairly well established that Grade I injuries probably do not need surgical repair and will likely resolve with conservative management where progression to rupture is highly unlikely.7,8 Conversely, patients with Grade IV or free rupture frequently do not make it to the hospital alive, and if they do, they are usually in extremis and require emergent treatment. Patients with Grade II to III fall into a “grey zone”. Some groups have shown that patients with Grade II injuries can be safely watched to allow appropriate stent graft sizing and stabilization of the patient before repair and, in fact, may not need repair at all.6,9 There is a paucity of data available on patients with Grade III injuries. The Society for Vascular Surgery consensus guidelines on TEVAR for blunt aortic injury recommends “urgent” (<24 hours from injury) repair of all thoracic aortic injuries immediately after other injuries have been repaired.6 We hypothesized that delayed repair of thoracic aortic injuries in patients with Grade III injuries could be performed safely with no increase in aortic-related morbidity and mortality, thus optimizing patient stabilization and allowing other more urgent operative management to take precedence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective review of all patients undergoing TEVAR for blunt aortic injury from March 2004 to March 2012 was performed. All procedures were performed at a single institution by one of five full-time academic surgeons. Our center is the only Level I trauma center in the state, and during this period, there

J Trauma Acute Care Surg

Volume 80, Number 61

were 10,621 trauma patients admitted. The timing of the procedure, choice of stent graft used, and all intraoperative decisions were at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Exclusion criteria included patients who had an open repair of their thoracic aorta; those with Grade I, II, or IV injuries; or those who lacked preoperative computed tomographic (CT) images with adequate detail to accurately measure injury morphology. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Informed consent was not obtained because this was a retrospective review and patients were not subjected to further tests or invasive procedures.

The trauma registry as well as individual patient charts and medical records were reviewed for demographic information, intraoperative variables and timing of aortic repair in relation to injury, coexisting injuries (based on International Classification of Diseases—9th Rev. coding) and operative repairs of these injuries, and 30-day postoperative events and mortality. Patients were placed into one of two groups, namely, those who were repaired immediately (within 24 hours of arrival) and those who were repaired in a delayed manner (>24 hours after arrival). Imaging that was reviewed included preoperative and postoperative CT angiography (CTA) as well as all intraoperative angiography. Preoperative CTA was used to assess grade of aortic injury and suitability for endovascular repair. Intraoperative angiography was reviewed to identify location of the endograft in relation to the left subclavian artery and the persistence of any obvious endoleaks before completion.

All cases were performed under general anesthesia using a mobile C-arm system or more commonly through a fixed fluoroscopy unit in a hybrid operating room. Device sizing was at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Deployment of the device with coverage of the aortic injury was the intent in every case. Some cases required planned left subclavian coverage to obtain adequate seal. The surgical approach was either through percutaneous access using the Perclose ProGlide (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) closure device and a “preclose” technique10 or via open cut-down. Infrequently, an iliac artery conduit was used for delivery of the device. These decisions, again, were

all at the discretion of the operative surgeon. Heparin was used during placement of large sheaths; however, it was reversed as soon as the sheaths were removed. Intravascular ultrasound was used during deployment for sizing at the discretion of the surgeon and was not performed routinely. We did not revascularize any left subclavian arteries prophylactically.

Grading on Imaging

All emergent patients with suspected chest trauma underwent CTA initially. The initial diagnosis was based on CTA, and no patient underwent conventional arteriogram for diagnostic purpose. Based on preoperative CTA imaging, patients were classified into one of four categories, dependent on severity of injury. Grade I injuries consisted of aortic intimal tear; Grade II had intramural hematoma; Grade III had aortic pseudoaneurysm, and Grade IV had free aortic rupture. Size of the pseudoaneurysm and presence of mediastinal hematoma was noted. Grade I injuries were routinely managed medically with repeat imaging to assess progression of injury and in the absence of progression were not repaired. Grade II and higher injuries were offered TEVAR if anatomically and clinically suitable. For the purposes of this study, we limited evaluation to Grade III injuries only.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics and outcomes were compared between the immediate repair group and the delayed repair group. Categorical data were analyzed using a contingency table with Fisher's exact test and two-tailed p values. Because of small sample size, nonparametric tests were used to analyze variables with skewed distribution. Mean with range was used instead of SD. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad (La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

During this period, 43 patients were admitted with blunt aortic injuries. Of these, nine had Grade I injuries and were

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of patients selected retrospectively for study.

J Trauma Acute Care Surg

Volume 80, Number 62

Table I.Demographics of Patients in the Immediate Repair and Delayed Repair Groups

Immediate Repair, n = 10, Mean (Range)

Delayed Repair, n = 13, Mean (Range)

p

Age, y

45.5

42.4

0.68

Male, n (%)

8/10 (80)

9/13 (69)

0.66

GCS score on arrival

8 (3–15)

10.8 (3–15)

0.31

ISS on arrival

38 (16–57)

41 (29–66)

0.55

Additional trauma diagnosis

71

147

Additional diagnosis per patient

7.1 (2–15)

11.3 (3–15)

0.01

Orthopedic injury, n (%)

4/10 (40)

11/13 (84)

0.04

Head injury, n (%)

5/10 (50)

5/13 (38)

0.69

Intra-abdominal injury, n (%)

5/10 (50)

11/13 (84)

0.17

Intrathoracic injury, n (%)

9/10 (90)

13/13 (100)

0.43

Spinal injury, n (%)

4/10 (40)

7/13 (53)

0.68

No. areas injured

2.7

3.6

0.1

CT imaging

Presence of mediastinal hematoma

9/9*

11/13

0.49

Maximum size of pseudoaneurysm, mm

32.6 (27.1–39.4)

29.9 (25.2–37.2)

0.14

Size of the proximal aortic landing zone, mm

24.7 (20.0–29.2)

23.0 (20.0–27.1)

0.17

Ratio of pseudoaneurysm to aorta

1.32

1.30

0.80

*Adequate CTA imaging was only available in 9 of the 10 patients in the immediate repair group. The data were reported in mean with distribution of minimum and maximum range. Nonparametric analysis: Wilcoxon rank-sum with continuity correction.

managed medically. Thirty-four patients had Grade II or higher injuries, of which two were repaired with an open procedure and excluded from the analysis and one was deemed not an endovascular candidate secondary to anatomy. He declined open surgery as well and was ultimately discharged and lost to follow-up. Three patients with Grade II injuries were treated with TEVAR, while two patients had Grade IV injuries that were treated with TEVAR. The remaining 26 patients all had Grade III blunt aortic injury according to the Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines.6 Of the 26 patients with Grade III injuries, 10 (38%) underwent TEVAR urgently (within 24 hours), while 16 (62%) had initial observation. The majority of those in the second group (13 of 16, 81%) ultimately had TEVAR in a delayed fashion, while three (19%) died of other injuries while in the hospital. These three patients had polytrauma with severe closed head injuries (Fig. 1). None of these deaths were caused by aortic pathology. Mean length of time until repair was 20 days, with a median of 9 days range, 2–91 days). For analysis, we have included 13 of the 16 patients because 3 died of other causes before TEVAR.

When comparing the immediate repair group and the delayed repair group, sex, age, grade of aortic injury, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score on arrival, and Injury Severity Score (ISS) were similar (Table 1). In all patients with Grade III aortic injuries, there were 218 additional trauma diagnoses. Despite similar ISS and GCS score, there were higher number of trauma diagnosis per patient in the delayed repair group as compared with the immediate repair group (11.3 vs. 7.1, p = 0.02). Both groups had similar number of patients with head, intra-abdominal, intrathoracic, and spinal injuries. However, there were significantly more orthopedic injuries in the delayed repair group than the immediate repair group (11 of 13 vs. 4 of 10, p = 0.04). Adequate quality imaging was available to review in all patients but one in the immediate repair group. There was no difference in size of pseudoaneurysm or ratio

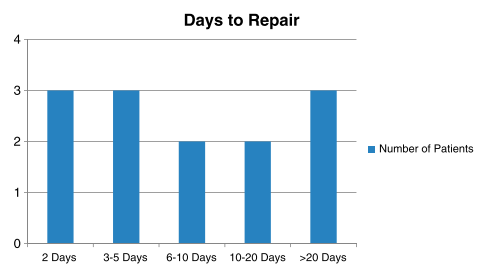

of pseudoaneurysm to normal proximal aorta between the immediate repair group and the delayed repair group. In addition, mediastinal hematoma was present in nearly all patients with no difference between groups. With regard to the TEVAR procedure itself, there was no significant difference between the groups in the graft used, number of patients with subclavian artery coverage, frequency of percutaneous access, or iliac conduit use (Table 2). Patients in the delayed group were repaired at a median of 9 days (range, 2–91) with 10 patients repaired at greater than 10 days from arrival (Fig. 2). The majority of patients in the delayed repair group had other surgical procedures performed before TEVAR compared with the immediate repair group, where TEVAR was performed as the initial trauma procedure. Significantly more patients had procedures performed before their TEVAR in the delayed group compared with the immediate repair group (11 of 13 vs. 4 of 10, p = 0.04). Of the 11 patients in the delayed repair group with operations performed before TEVAR, there were 24 procedures

Table II.Operative Variables of the Immediate and Delayed Repair Groups

Immediate Repair (n = 10)

Delayed Repair (n = 13)

p

Days to repair (range)

0.3 (0–1)

20.2 (2–91)

0.04

Graft manufacturer

Gore

6

9

0.69

Cook

3

3

1.0

Medtronic

0

1

1.0

Custom built

1

0

1.0

Subclavian coverage

2

2

1.0

Percutaneous

1

0

0.43

Iliac conduit

2

7

0.2

J Trauma Acute Care Surg

Volume 80, Number 63

Fig. 2 Days to repair in the delayed repair group.

performed. Of the 11 patients, 8 had one or more orthopedic procedures performed. Four patients had one or more abdominal operations performed, and seven patients had other operative procedures performed before TEVAR (Table 3). Of the 11 patients, 6 had more than one procedure performed before their TEVAR.

Three of the four patients in the delayed died and had not undergone TEVAR yet (thus 13 of 16 had delayed TEVAR). However, none of the deaths were related to aortic injury. Of the 13 patients originally in the delayed repair group, there was 1 death within 30 days after the TEVAR, again not related to aortic injury. This was not significantly different from that in the immediate repair group, where there was one death within 30 days of arrival. The death in the immediate repair group was related to other injuries and not to aortic pathology as well.

In addition, only 1 of the 13 patients in the delayed repair group that underwent repair had a change in their CT scan before repair. In this patient, there was increasing free fluid noted in a follow-up chest CTA performed for other reasons, and repair was performed immediately after detection of the change. Angiography did not show leak or rupture, there was no morbidity or mortality associated with this change, and the patient underwent successful TEVAR. Length of stay was longer in the delayed repair group (16 days vs. 24 days, p = 0.16), although this failed to reach statistical significance (Table 4). There were two patients in the delayed group where TEVAR was performed at Days 82 and 91 after the initial injury. Both these

Table III.Other Procedures Performed Before TEVAR in the Immediate Versus Delayed Repair Groups

Immediate Repair (n = 10)

Delayed Repair (n = 13)

p

Patients with procedure before or simultaneously with TEVAR?

4/10

11/13

0.04

Type of procedure before TEVAR

Orthopedic

0

8/11

0.003

Abdominal

3

4/11

1.0

Diagnostic

1

1/11

1.0

PEG/Trach

0

4/11

0.10

Other

0

2/11

0.49

Multiple procedures before

0

6/11

PEG, percutaneous gastrostomy; Trach, tracheostomy

Table IV.Survival and Length of Stay in the Immediate and Delayed Repair Groups

Immediate Repair (n = 10)

Delayed Repair (n = 13)

p

Change in injury grade before repair

0/10

16 (1–41)

9/10

Length of stay* (range)

1/13

27 (5–42)

12/16

30-day survival

0.08

0.62

*Excludes two patients who were discharged and returned for aortic surgery

patients had scheduled CTA at the time of discharge and then at 30-day intervals. One of these patients underwent repair at Day 91 because of a slight increase in the size of the pseudoaneurysm. The other patient underwent repair electively with no change in the size. We had recommended TEVAR to both patients earlier, but they had initially declined surgery.

DISCUSSION

Patients with blunt aortic injury rarely have isolated vascular trauma. In our series, patients with Grade III injuries had on average 9.5 trauma diagnoses per patient, with the patients in the delayed repair group having a higher number of trauma diagnoses compared with the immediate repair group (11.3 vs. 7.1), despite similar ISS and GCS score on arrival. These patients are commonly in shock and have multiple injuries that need to be stabilized and addressed simultaneously. There is frequently a question of which injury should be addressed first, and often significant time in the operating room is required to handle all the surgical problems. Several earlier studies looking at blunt aortic injuries found that delayed repair of aortic injuries may be associated with improved survival regardless of associated injuries.11–13 However, these studies did not have the patients divided by aortic injury grade, and thus, generalization to higher-grade injuries could not be made. These suggest that patients with Grade III blunt aortic injury can be safely watched and stabilized before definitive repair. An “emergent” repair of the aorta is certainly necessary with a Grade IV injury of the aorta or a change in the initial grade of the aortic injury, but we found no difference in Grade III patients who had their aortic injuries repaired immediately (within 24 hours) or in a delayed fashion. In addition, there are perceived benefits to waiting for aortic repair. It allows not only repair of other injuries in a timely fashion but also stabilization of the patient and adequate resuscitation, which may aid in graft sizing.8 In our small series, there was no significant difference in aortic neck diameter between the CTA obtained on arrival and any repeat CTA performed before definitive repair. In addition, a recent article by Rabin et al.13 suggests that early aortic repair may worsen concurrent traumatic brain injury, and thus, a delayed strategy for blunt aortic injury may be warranted.

Of 16 patients, 3 died of their other injuries before definitive aortic repair in the delayed repair group. In addition, one patient in the delayed group had undergone a successful TEVAR and died of other injuries. We had no aortic-related deaths in either group, and only one patient in the delayed group had a change in aortic pathology before definitive aortic repair. In this patient, respiratory issues developed, and

J Trauma Acute Care Surg

Volume 80, Number 64

repeat CT suggested increasing free fluid in the chest. He was taken urgently for TEVAR and ultimately did well. The vast majority of our patients underwent repair on the same admission, but 2 of the 13 patients in the delayed group had significant delays in their repair after being discharged and brought back for definitive repair (82 days and 91 days, respectively). They were followed up with scheduled CTA and were underwent repair electively. One of them had a slight increase in size of the pseudoaneurysm and underwent elective repair. The other patient had been advised and finally agreed to the repair with no change in size. This is a very small subset of patients and do not represent the norm. Our practice is to repair the Grade III patients before discharge from their initial hospitalization.

Our group practice has thus developed a strategy of watchful waiting for blunt aortic injury from Grade I to III injuries. These patients are resuscitated in the intensive care unit with anti-impulse therapy with β-blockers while monitoring blood pressure and pulse as their other trauma issues are addressed. Our goal is to keep the mean pressure to less than 70 mm Hg. This is achieved with judicious use of β-blockers. Once the patient is fully resuscitated, a repeat CTA is obtained at 48 hours for more accurate sizing and to monitor any progression of aortic pathology. Repeat imaging is then obtained as clinically indicated, and repair then takes place just before the patient is ready for transfer out of the intensive care unit.

Limitations of our research are related to the small sample size of the patient population, the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that it was performed at a single center.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, repair of Grade III aortic injuries may be safely delayed to allow optimal resuscitation and management of coexisting trauma injuries. These patients should have strict blood pressure control with anti-impulse therapy and invasive blood pressure monitoring. Further study in a prospective manner at multiple institutions would be beneficial in determining the optimal treatment of patients with these devastating injuries.

AUTHORSHIP

M.R.S. and A.T.A. were involved with the study design and data interpretation. M.R.S. and A.T.A. also performed initial analysis and wrote the manuscript. M.P.W. was involved with the data collection. M.M.M., J.F.E., and G.A.E. provided critical revisions. H.J.S. was involved in the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Demehri S, Rybicki FJ, Desjardins B, Fan CM, Flamm SD, Francois CJ, Gerhard-Herman MD, Kalva SP, Kim HS, Mansour MA, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria blunt chest trauma—suspected aortic injury. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19:287–292.

- Murad MH, Rizvi AZ, Malgo R, Carey J, Alkatib AA, Erwin PJ, Lee WA, Fairman RM. Comparative effectiveness of the treatments for thoracic aortic transection. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:193–199.

- Celis RI, Park SC, Shukla AJ, Zenati MS, Chaer RA, Rhee RY, Makaroun MS, Cho JS. Evolution of treatment for traumatic thoracic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:74–80.

- Azizzadeh A, Keyhani K, Miller CC, Coogan SM, Safi HJ, Estera AL. Blunt traumatic aortic injury: initial experience with endovascular repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1403–1408.

- Azizzadeh A, Chralton-Ouw KM, Chen Z, Rahbar MH, Estrera AL, Amer H, Coogan SM, Safi HJ. An outcome analysis of endovascular versus open repair of blunt traumatic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:108–115.

- Lee WA, Matsumura JS, Mitchell RS, Farber MA, Greenberg RK, Azizzadeh A, Murad MH, Fairman RM. Endovascular repair of traumatic thoracic aortic injury: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:187–192.

- Osgood MJ, Heck JM, Rellinger EJ, Doran SL, Garrard CL, Guzman RJ, Naslund TC, Dattilo JB. Natural history of grade I–II blunt traumatic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:334–341.

- Jonker FH, Verhagen HJ, Mojibian H, Davis KA, Moll FL, Muhs BE. Aortic endograft sizing in trauma patients with hemodynamic instability. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:39–44.

- Rabin J, DuBose J, Sliker CW, O'Connor JV, Scalea TM, Griffith BP. Parameters for successful nonoperative management of traumatic aortic injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:143–149.

- Lee WA, Brown MP, Nelson PR, Huber TS. Total percutaneous access for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (“Preclose” technique). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1095–1101.

- Demetriades D, Velmahos GC, Scalea TM, Jurkovich GJ, Karmy-Jones R, Teixeira PG, Hemmila MR, O'Connor JV, McKenney MO, Moore FO, et al. Blunt traumatic thoracic aortic injuries: early or delayed repair— results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma prospective study. J Trauma. 2009;66:967–973.

- Reed AB, Thompson JK, Crafton CJ, Delevecchio C, Giglia JS. Timing of endovascular repair of blunt traumatic thoracic aortic transections. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:684–688.

- Rabin J, Harris DG, Crews GA, Ho M, Taylor BS, Sarkar R, O'Connor JV, Scalea TM, Crawford RS. Early aortic repair worsens concurrent traumatic brain injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:46–52.

3/10/2021

Matthew R. Smeds, MD, Mark P. Wright, MD, John F. Eidt, MD, Mohammed M. Moursi, MD, Guillermo A. Escobar, MD, Horace J. Spencer, and Ahsan T. Ali, MD

Published 2016

Matthew R. Smeds, MD, Mark P. Wright, MD, John F. Eidt, MD, Mohammed M. Moursi, MD, Guillermo A. Escobar, MD, Horace J. Spencer, and Ahsan T. Ali, MD

Delayed management of Grade III blunt aortic injury: Series from a Level I trauma center

Summary

This study reviews a single center's experience comparing urgent (<24 hours) thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR) versus delayed (>24 hours) TEVAR for Grade III BAI. BAIs (Blunt aortic injuries) are dangerous & need to be treated asap.

This has improved survival and decreased the risks of dreaded complications such as spinal cord ischemia, renal failure, and systemic infections.