-

Case Report:

Esophageal Stent Erosion into the Common Carotid Artery

Ahsan T. Ali, MD, Mimi S. Kokoska, MD, Eren Erdem, MD, and John F. Eidt, MD

Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Volume X Number X

Month 2007 1-3

© 2007 Sage Publications

10.1177/1538574406297256

http://ves.sagepub.com

hosted at http://online.sagepub.com

A pseudoaneurysm of the common carotid artery was found with computed tomography in a 62-year-old woman with an esophageal stent that had eroded through her skin. The pseudoaneurysm was treated with a self-expanding nitinol stent; after massive hemoptysis, an endograft was placed on the pseudoaneurysm. The patient then under- went ligation of the left common carotid artery, proximal

to the carotid bulb, and excision of the endograft and previously placed coils. The esophageal stent wires were so that they could no longer impinge the common carotid artery.

Keywords: arterial infections; common carotid artery; endograft; pseudoaneurysm

A 62-year-old woman presented with dysphagia that rapidly progressed to complete obstruc- tion in January, 2005. Surgical history was sig- nificant for a total laryngectomy and a selective left neck dissection for laryngeal carcinoma with radia- tion therapy. She also underwent a primary tracheoe- sophageal puncture for speech rehabilitation. The tracheoesophageal puncture continued to enlarge into a large tracheoesophageal fistula. An esophageal stent (Boston Scientific Company) was placed to span the fistula.

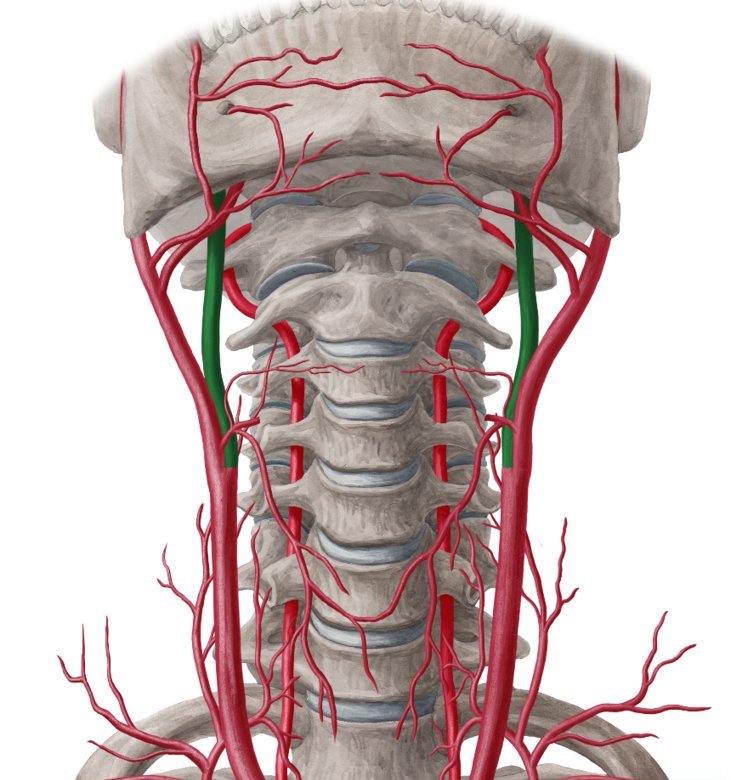

In January 2005, her family noted that the esophageal stent started to erode through the skin. An open gastrostomy tube was placed. A computed tomography scan revealed a pseudoaneurysm in her left common carotid artery caused by gradual migra- tion of the proximal portion of the esophageal stent (Fig. 1). Cerebral angiography revealed adequate cross-filling from right-to-left side. The patient tol- erated a 30-minute balloon occlusion test of the left internal carotid artery with no neurological deficit. This was part of a workup for possible ligation of the common carotid artery. The pseudoaneurysm was

From the Division of Vascular Surgery (ATA, JFE), Department of Surgery; Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery (MSK); Division of Neuroradiology (EE), Department of Radiology; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Address correspondence to: Ahsan T. Ali, MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham Street, Slot #520-2, Little Rock, AR 72205; tel: 501-686-6176; fax: 501-686-5328; email: aali@uams.edu.

Figure 1. Computed tomography angiogram of the neck shows t

also evident (Fig. 2). A self-expanding nitinol stent was placed, and the pseudoaneurysm was coiled through the interstices of the stent. Two weeks later, the patient presented with massive hemoptysis. She was urgently rushed to the angiography suite (Fig. 3), where the pseudoaneurysm was covered by an endo- graft (WallgraftTM) (Fig. 4). Three days later, she was taken to the operating room where she underwent

2 Vascular and Endovascular Surgery / Vol. X, No. X, Month 2007

Figure 2. Arteriogram of the pseudoaneurysm of the common carotid artery before stent and coiling.

Figure 4. Arteriogram of a covered endograft placed in the common carotid artery to stop the massive hemorrhage.

Figure 3. Arteriogram 2 weeks after the coiling; the esophageal stent eroded again into the common carotid artery.

Figure 5. At surgery, the common carotid artery bleeding is controlled. Note the proximity of the tracheostomy.

ligation of the left common carotid artery, proximal to the carotid bulb and excision of the endograft and the previously placed coils (Figs. 5-7). The esophageal stent wires were trimmed approximately 1.5 cm. The wires were cut so that they could no longer impinge

Esophageal Stent Erosion into CCA / Ali et al 3

Figure 6. Ligation of the common carotid artery with removal of the stent and the endograft.

on the region of the common carotid artery. The remaining length of esophageal stent was left in place because it incorporated well. Methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus grew on the graft, and the patient was placed on antibiotics for 4 weeks. She was placed on coumadin for 6 months.

Discussion

There is a higher incidence of graft disruptions involving autogenous bypass in the neck than in any other vascular bed.1 In this case, the initial approach was to treat the pseudoaneurysm but not the under- lying cause. This resulted in a reoccurrence 2 weeks later. In a hostile environment such as an irradiated neck or in patients with chronic infection or leaks, carotid artery ligation may be the safest option. To achieve this, it is essential to obtain the arteriogram

Figure 7. Removal of the coils.

delineating the anatomy as well as the flow dynam- ics during cross-filling. The status of the anterior communicating and the posterior communicating arteries can be assessed. This allows for primary lig- ation as the initial approach. In a scenario, where the patient has no adequate cross-filling and a hos- tile neck environment, bypass can be a risky option. However, ligation of the common carotid artery is a safer option than the ligation of the internal carotid artery as far as risk of postoperative stroke is con- cerned. If possible, a pectoralis muscle flap is a good option when coverage is required.

Reference

1. Ali AT, Bell C, Modrall JG, Valentine RJ, Clagett GP. Graft-associated hemorrhage from femoropopliteal vein grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:6667-6672.

3/10/2021

Ahsan T. Ali, MD, Mimi S. Kokoska, MD, Eren Erdem, MD, and John F. Eidt, MD

Published 2007

Ahsan T. Ali, MD, Mimi S. Kokoska, MD, Eren Erdem, MD, and John F. Eidt, MD

Esophageal Stent Erosion into the Common Carotid Artery

Summary

A patient who had previously had surgery to remove laryngeal tumor was experiencing difficulty in swallowing. When examined it was revealed that the oesophageal stent which was helping her speak, was protruding into her common carotid artery.

This caused a pseudoaneurysm which was treated by placing a nitinol stent. This led to her coughing up blood 2 weeks later because the cause of the pseudoaneurysm was not treated. It was just covered up with a stent.

What ultimately helped her is cutting out the extra length of the esophageal stent wires. This made sure that the wires were not protruding into the common carotid artery and the hole in the artery was stitched up.